Vulgar Vignettes

Today, there are only a few remaining movie theaters in New Orleans. But just a few decades ago, downtown movie palaces like the Joy and Saenger competed for audiences with neighborhood cinemas from the Marigny to Carrollton.

What's less remembered is a brief period mostly in the 1970s when mainstream and art house theaters began switching to a new type of entertainment: pornography. It was part of a nationwide boom in erotically focused movie theaters, as audiences became more accepting of and curious about sexual content, downtown cinemas looked for ways to compete with color TV and drivable suburban theaters, and a series of court rulings strengthened First Amendment protections and made prosecuting pornography under obscenity laws more difficult.

In New Orleans, they were present in prime locations around the city, and their advertisements were ubiquitous in local mainstream and alternative papers. Discussions about the morality, artistic merit, and legality of the movies they showed entangled and baffled arts critics, the general public, and the legal system, with New Orleans police officials once screening more than three hours of seized porn for reporters so they could understand just how filthy it was.

(left) Ad for “The Virgin & the Gypsy” playing at the Toulouse Theater in 1970; (right) The Toulouse Theater today.

In 1970, for example, The Times-Picayune reported that the “French Quarter’s new art film house, Toulouse Cinema,” was slated to open with a showing of The Virgin and the Gypsy, a Cannes-exhibited drama based on a D.H. Lawrence novel.

Over the next few years, the theater—at 615 Toulouse St., home to the current Toulouse Theater and, in recent years, to One Eyed Jack’s and the Shim Sham Club—would screen W.C. Fields and Charlie Chaplin classics, the anti-imperialist thriller State of Siege, and Luis Buñuel’s surrealist classic The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, which a States-Item critic called “confusingly satirical” albeit “a lot of fun.”

But by 1974, the theater was primarily advertising a different sort of film: Deep Throat, The Devil in Miss Jones, and later French Blue, Cheese, and Illusions of a Lady, all listed with a rating of “X.” The theater had become just one of a number of porn-focused entertainment spots at prime locations in and around the French Quarter, including some longstanding theaters and others that popped up amid the porno boom.

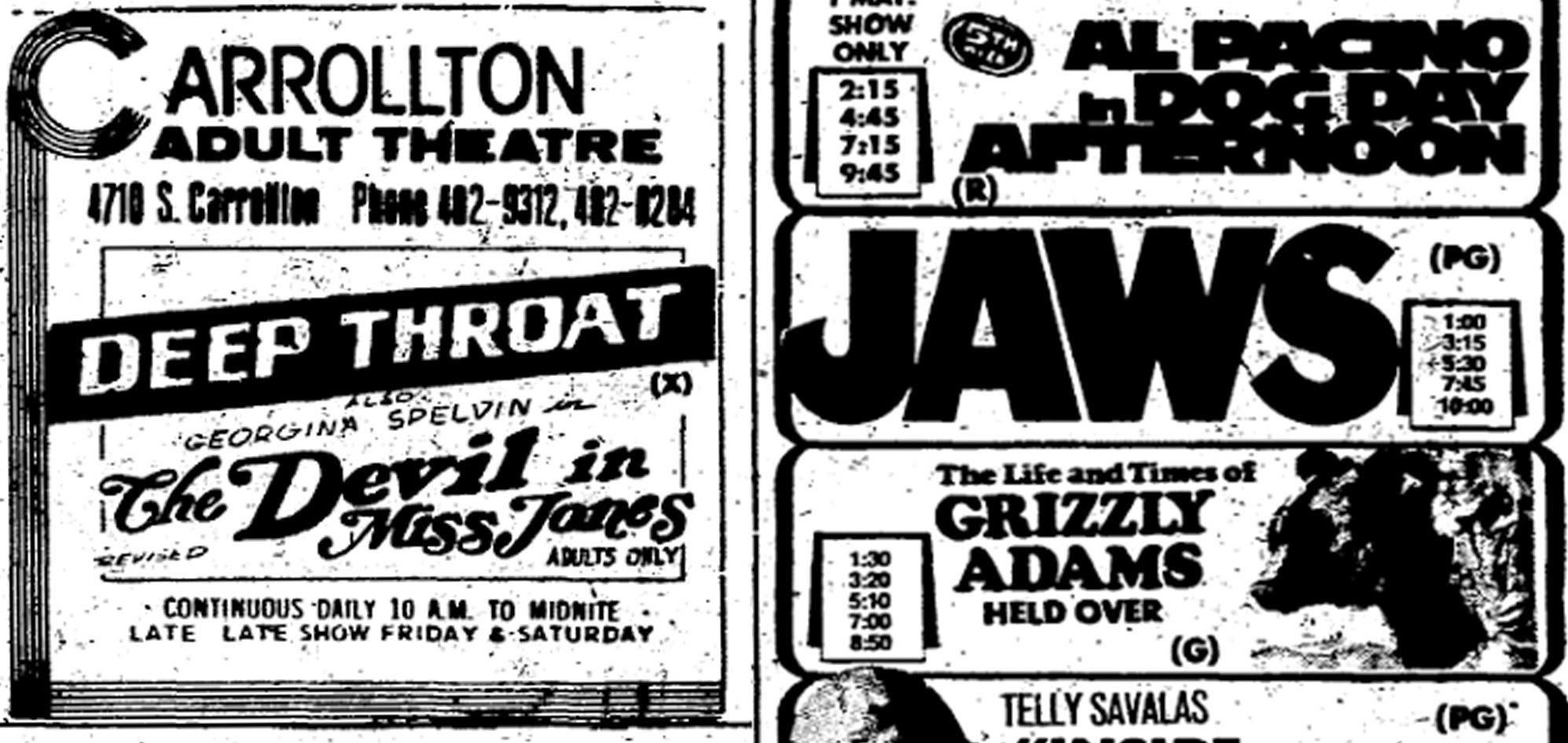

Ad in a 1976 Times-Picayune for “Deep Throat” and “The Devil in Miss Jones” double feature at the Carrollton Adult Theater.

Adult cinemas—many of them traditional and art theaters that switched to erotic fare amid declining audience sizes—were seldom listed in tourist guidebooks and don’t often turn up in today’s lists of Vieux Carre locales that ain’t dere no more.

But in addition to the Toulouse Cinema, there was the Caprice Theater at 127 Chartres St., which advertised free admission to women with male escorts. There was the Pussycat Theatre, which boasted of showing “the most exciting adult films” at 405 Bourbon St., now home to a souvenir shop called Jazz Funeral. Just down the street, at 333 Bourbon, was a branch of Ellwest Stereo Theatres; the site is now the location of Prohibition Bar, “home of Huge Ass Beers.” At 519 Iberville St., now occupied by condos, the d’Iberville Theatre showed “Triple X Features” from 10 a.m. through 2 a.m. The grandly named Les Banque Cinema

Fantastique—sometimes just advertised as “The Bank”—showed adult movies in the former bank building at 941 Decatur St., which after a stint as the ‘90s counterculturish coffeehouse Kaldi’s is now a tour guide office. Ramrod Cinema screened “all male movies” for a time at that same location, and the St. Peter St. Book Mart showed “adult mini theatre shows in blushing colour” for 25 cents, 24 hours a day at 730 St. Peter St., near the corner of Bourbon.

Advertisements appearing in 1975 Times-Picayune for a myriad of porn theaters across the city.

A 1975 feature in Dixie, then the Times-Picayune’s magazine section, cited a dozen New Orleans theaters that had pivoted from traditional popcorn fare to porn, and a States-Item story from the same year suggested that New Orleanians would soon “only have one choice when they go to the movies: Which nude bodies do they want to watch?”

It’s clear from these and other stories at the time that New Orleans reporters, and perhaps their audiences, were as confused by the seemingly sudden burst of erotic cinema as they were by Buñuel. Dixie reporter Becky Bruns visited a porn theater and interviewed an audience member who “fits the common image of the pornwatcher, the overweight misfit with nowhere to go but behind dull eyes and a freckled double chin.” But she also described first-time viewers, including a “youthful middle-aged couple” from “up North” and a “plump, single black woman” who “prefers regular movies,” seemingly emphasizing that people not unlike the reader and writer were going to see porn.

A 1971 States-Item report chronicled entertainment editor James A. Perry’s visit to two adult theaters: the Caprice, and Cinema 16, at 1014 Canal St. (now home to vacation rentals). Unusually, the piece appears without a byline and cites Perry as a source, after beginning by describing an ad for an adult theater that ran in the Tulane Hullabaloo.

“It promotes a product,” reported the States-Item. “That product is SEX.”

The unnamed author of the piece also quoted police officers described as hamstrung by the complex juridical frameworks around legal censorship as they try “to combat obscenity and its nightmarish satellites,” as well as managers of the Orpheum, Joy, and Saenger theaters—all of whom then still showed Hollywood movies and claimed their customers wouldn’t be interested in erotic cinema. Intriguingly, the quotes from Perry himself seemed surprisingly accepting.

“I was amazed to find that the vulgar vignettes featured attractive ‘actors,’ and in several cases, extraordinarily beautiful specimens,” he said. “I had expected tired, worn-out people in ancient film clips. Not so. It’s a modern setup, all the way.”

And while the article expressed seeming shock at the Hullabaloo running ads for porn theaters, the States-Item, the Times-Picayune, and the alternative paper NOLA Express would within a few years all be regularly running ads for such establishments. Some ads even seemed to mock the typical criticisms of pornographic movies.

“No Plot,” read one ad for a screening of Female Frenzy of Dr. Studley at the Cinne Arts theater at 3928 Clematis St. “But oh those Beautiful Girls.”

Still, obscenity laws remained on the books, and 1970s newspapers regularly reported on police raids at pornographic theaters and bookstores offering peep shows or erotic magazines. Sidney’s, the French Quarter liquor store that then operated as a newsstand, faced charges in 1977 for selling purportedly obscene periodicals. NOLA Express successfully challenged a federal indictment for obscenity in 1970 after running an explicit, feminist parody of Playboy’s “What Sort of Man Reads Playboy” ad campaign. (The satirical piece, which mocked a series of ads depicting stylish, successful men as readers of the magazine, showed a man in a dingy room masturbating to pinned-up Playboy centerfolds above that “What Sort of Man…” tagline.) In successful prosecutions of theaters and adult bookstores, owners and employees sometimes received only a small fine, but in other cases multiyear sentences at Angola and federal prisons were handed down, and theaters were at times ordered closed. Names and even home addresses of theater and bookstore employees who were arrested, including many low-level and often young workers like projectionists and ticket takers, were routinely printed in the local press.

Though they could certainly be high stakes for business owners and employees, prosecutions also often had a tendency to turn farcical. One series of court decisions involved challenges to a confusingly worded state obscenity statute that at one point erroneously referred to “the exhibition or sale of obscure materials,” rather than “obscene” ones. A lawyer for a porn theater was held in contempt in 1972 after he failed to bring an allegedly obscene film called “Law and Disorder” to court; he said he simply accidentally brought the wrong movies. Another case saw a federal indictment thrown out for violating grand jury secrecy rules: While a set of seized pornographic movies were being screened for grand jurors at a downtown hotel equipped with a film screening room, FBI Agent Richard Bacon impermissibly entered the room and watched some of the porn alongside the jurors. He said he did so “to satisfy his own curiosity as to how the 35 mm projector operated.”

(Left) Archival photo of the since demolished Paris Theatre & (right) contemporaneous advertisement in the Times-Picayune for its XXX features.

Paradoxically, the process of prosecuting porn purveyors showing movies to consenting adults often required more porn screenings, often for judges and jurors who claimed to have no interest in seeing the material. One California judge, fed up with having to review allegedly obscene movies with little plot, made headlines in 1978 after sentencing a theater owner to watch four hours of porn a week for a year. That same year, the States-Item reported that jurors hearing an obscenity case against the president of the parent company of the Paris Theatre at 900 Elysian Fields Ave. watched “two hours of explicit sex” but that “no member of the jury panel fainted or vomited, as had happened before.” In a case against the Caprice Theater, a judge was forced to delay proceedings because no projector was available; he decreed the trial would be moved to the porn theater itself in order to watch its allegedly obscene films—as soon as the theater’s projector returned from a repair shop in Chicago.

Reporters were also subjected to porn screenings at at least one press conference in 1970, when the Times-Picayune reported that cops at police headquarters showed journalists three-and-a-half hours of pornography seized from the Cinne Arts Theater under municipal obscenity laws.

“An occasional lack of enthusiasm or spontaneity on the part of the actors did not blunt the raw sex appeal of these films,” an unbylined article reported.

And when a group called The Society to Oppose Pornography (S.T.O.P.) sued to close the Bank theater on Decatur Street under public nuisance laws, society president Gera Brupbacher testified she didn’t watch the allegedly obscene movies in question at the theater—only in municipal court, when one of the theater’s employees previously faced charges.

Brupbacher—a Lakeview swim coach who regularly wrote to local newspapers at the time using her married name, Mrs. B. S. Brupbacher —and STOP put out a newspaper of their own called Argus, which castigated judges for not doing more to shutter pornographic movie theaters. Argus delivered some of the most detailed reports of porn-related lawsuits and prosecutions and seemed to run far more photos of porn theater exteriors and marquees than any other outlet. It also regularly railed against hippies, drug users, and the publishers of alternative newspapers in editorials and bombastic political cartoons. At times, Argus complained that NOLA Express, which the paper called “a cheap pornographic rag edited by two undesirables in the French Quarter,” was being distributed at City Hall and at local high schools. In turn, Brupbacher became a frequent target of ire from NOLA Express and fellow alternative publication Logos.

“This issue NOLA Express dedicated to our ace public relations woman, Mrs B S Brupbacher, of the Lakeview Women’s Garden Club, who in her crusade against obscenities in NOLA Express has done wonders for our circulation,” read one note in NOLA Express. “Fuck you, Mrs B S Brupbacher.”

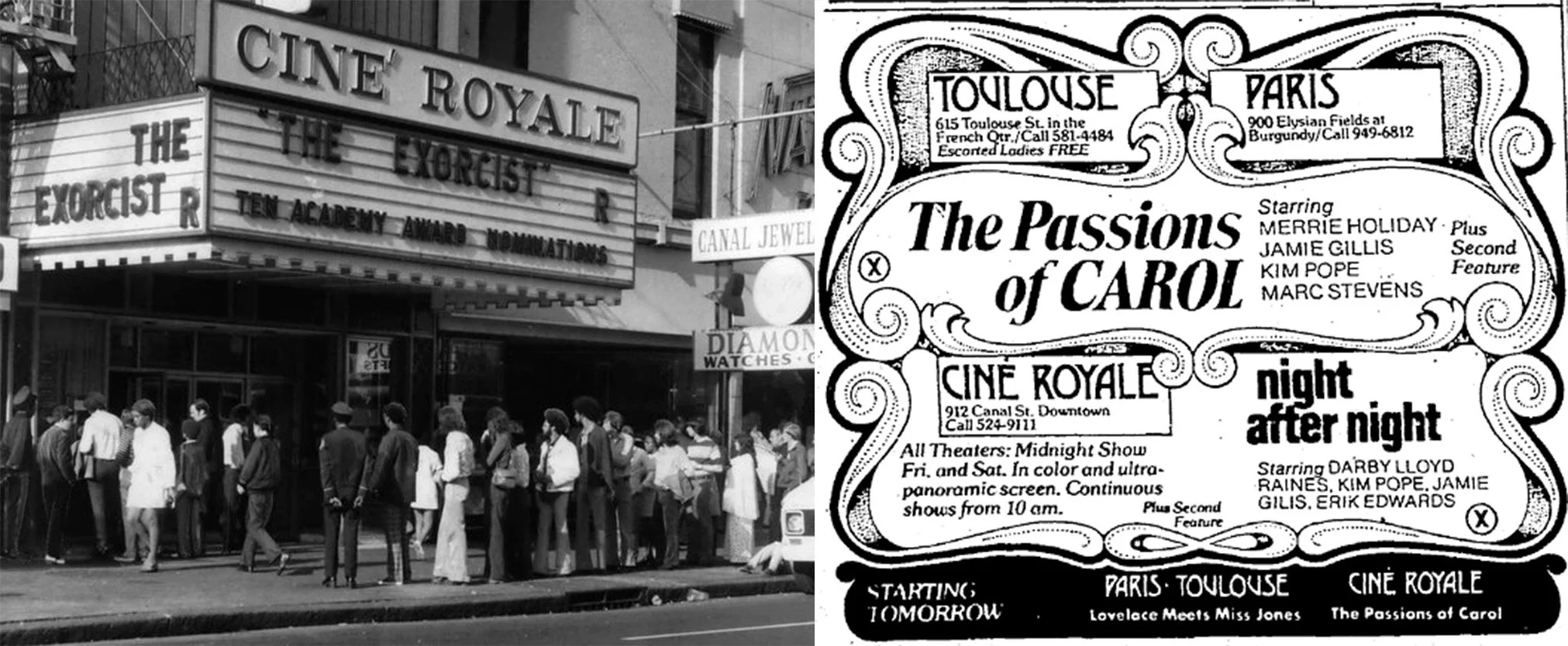

(Left) Attendees lined up to see “The Exorcist” at Cine Royale. (Right) Just a few years later the same venue advertises for adult films in the Times-Picayune.

But as farcical as many of the prosecutions turned out to be, continued police raids did take their toll on the New Orleans porn industry, as did the rise of the VCR, which made it possible for people to view porn (or other movies) at home. By 1988, Times-Picayune columnist James Gill wrote that the only remaining porn theater was Cine Royale at 912 Canal St, which was protected by a restraining order as it challenged the constitutionality of state obscenity laws. The theater finally closed in the 1990s, and it was torn down to make room for the expansion of the Walgreens at the corner of Canal and Baronne streets.

Today, while erotic material is more available and culturally acceptable than ever before, public porn cinemas are virtually extinct in New Orleans and around the country. The idea of going to watch porn in a theater with strangers is likely as distant to many New Orleanians as vaudeville or silent movies. In a city that usually strives to preserve its history, and where buildings and neighborhoods have no shortage of former artistic and performative uses, the adult theater era is largely a forgotten period.

…

Cover image created using a photo by John Michael Wilkinson.